0020: Image Buttons

We’ll do two things today:

- slap an image onto a button, and

- set up a mechanism to swap that image for another.

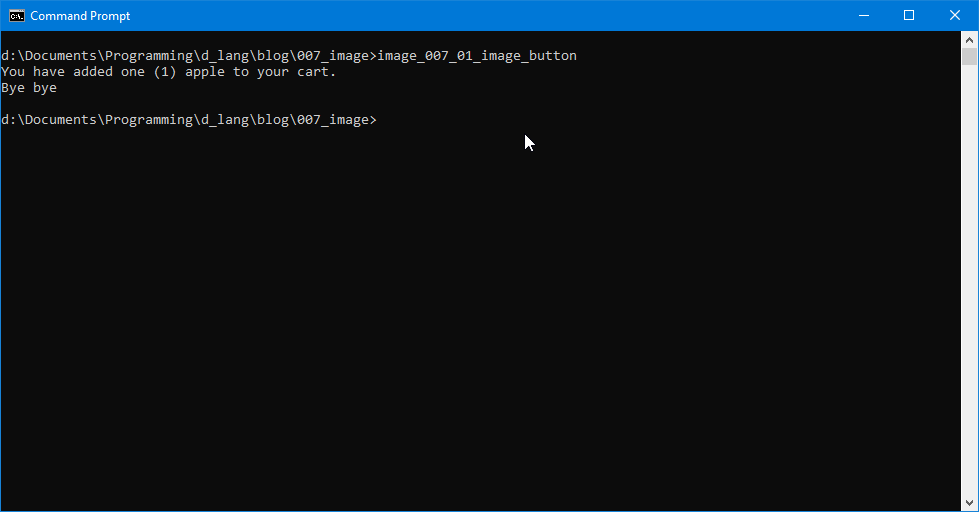

Image on a Button

There isn’t much in the way of preparation needed, just one extra import statement:

import gtk.Image;

Then load the image:

Image oranges = new Image(imageFilename);

And finally, add it to the button:

button.add(oranges);

But because we’re doing this in the usual way, in a derived class, it looks like this:

class ImageButton : Button

{

string imageFilename = "images/apples.jpg";

string actionMessage = "You have added one (1) apple to your cart.";

this()

{

super();

Image appleImage = new Image(imageFilename);

add(appleImage);

addOnClicked(&doSomething);

} // this()

void doSomething(Button b)

{

writeln(actionMessage);

} // doSomething()

} // class ImageButton

There is no deep meaning behind using an image of apples and calling it oranges. I’d call it a joke if it was actually funny. I’m explaining this to avoid any confusion.

Drop this class into the test rig window:

ImageButton myButt = new ImageButton();

add(myButt);

And that’s it for the coding side.

Don’t forget to create a directory (folder, in Windows speak) and place the image in there. And of course there’s nothing says you have to use the image I’ve provided or the naming convention I’ve laid out.

Path Names

It may cross your mind, if you’re doing this in Windows, that you have to swap out the UNIX forward slash ( / ) for the Windows backslash ( \ ) when you’re writing out the path/filename.

You don’t have to.

Compilers are OS-aware enough to know which way to slash. And as a side note, how do you remember which is which? I saw it explained like this:

- if a person leans forward, they look like a forward slash (UNIX),

- if a person leans backward, they look like a backslash (Windows).

When it comes to this incompatibility that has plagued cross-platform development since the dawn of the personal computer era, I won’t point any fingers. The person who came up with this knows who he is. ‘Nuff said.

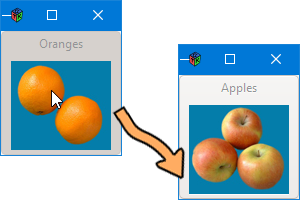

Swap an Image on a Button

The necessary differences with this example are twofold:

- we need a second image (you may say: well, duh), and

- we need a function to do the swapping.

But that hasn’t stopped me from throwing in some extra layers of complication. These are:

- an

InnerBoxclass (an observer) so we can have both a label and an image, - a

SwitchingImageclass (one of the observed) that does the work of swapping the image, and - a

SwitchingLabelclass (also observed by theInnerBoxobserver) that does the same for the label.

How it All Works

If you remember, a Button is actually a container type similar to a Window and that means:

- the

ImageButton(derived fromButton) contains one child widget:InnerBox, - the

InnerBox(derived from aBox) contains two widgets:SwitchingImage(derived fromImage), andSwitchingLabel(derived fromLabel).

And because InnerBox maintains pointers to its children, all this makes observation and action easy from within the InnerBox with its changeBoth() function:

void changeBoth()

{

switchingLabel.change();

switchingImage.change();

} // changeBoth()

SwitchingImage and SwitchingLabel each have similar-but-not-exactly-the-same change() functions. SwitchingImage’s looks like this:

void change()

{

if(current == apples)

{

current = oranges;

}

else

{

current = apples;

}

setFromFile(current);

} // change()

And the only difference with SwitchingLabel is the removal of this line:

setFromFile(current);

and replacing it with this:

setText(current);

And, of course, if you look closely at these change() functions you’ll see that the variable current is a string in both instances, but in one it’s a path/filename combination which in the other, it’s just text.

A Note Regarding Typing in Code Examples

If you type these in by hand (highly recommended for getting your memory to embrace this stuff) just make sure to get those import statements correct. All the GTK imports come from the gtk library except one: Event. It comes from the gdk library and if you type gtk instead of gdk, you’ll get a potentially-confusing compiler error:

module Event is in file ‘gtk/Event.d’ which cannot be read

But this is just a bump along the road to becoming a coder. And now you know about it.

Until next time, take care and may the good code be yours (points for knowing who I’m paraphrasing here).

Comments? Questions? Observations?

Did we miss a tidbit of information that would make this post even more informative? Let's talk about it in the comments.

- come on over to the D Language Forum and look for one of the gtkDcoding announcement posts,

- drop by the GtkD Forum,

- follow the link below to email me, or

- go to the gtkDcoding Facebook page.

You can also subscribe via RSS so you won't miss anything. Thank you very much for dropping by.

© Copyright 2024 Ron Tarrant